I’m changing my Spirit Animal

In recent years, I’ve been making it a practice to snap a photo of myself on my birthday as I ascend into the heady realm of old age. I turned 72 on July 10, which is supposed to be the new 40 or something if you’re up to date on the newest dietary supplements and anti-prostapocalypse Kegel exercises that keep you youngalike for decades longer than your dad. 70 is not the new 40 though. By coincidence, if there is such a thing, a young lady I’ve regarded as a daughter since I met her sent me a photo she found just last week.

She wasn’t trying to be unkind, just reminding me how long we’ve known each other. The years take their toll now, just as they always have. I don’t deny playing with the photos after I take them. My motives aren’t even pure. I’m trying to stage-manage the future, at least in part, because when they show us portraits of a long dead writer they tend to want us to see what they looked like toward the end, when all that narcissism, obsession, and collateral unruly behavior have exacted their visible price for the works bequeathed to us. When they want to convey the essence of Poe or Beethoven they give you as close to a portrait of a living corpse as they can find.

It’s important to keep game changers in their place, so people won’t be tempted to follow too closely in their footsteps. Poe never got to Photoshop himself for editors of the future, and Beethoven lived before photography, so they get to make him up more or less from scratch. Note, though, they have the same eyes, intense ‘way out there’ eyes. Why I also spent part of my birthday adjusting my snapshot into a slightly more dignified format in which the eyes remain a deliberate secret.

First things first though. The nerve. Poe? Beethoven? Who do I think I am? I’m the only actual writer who knows anything about Artificial Intelligence. I was still in my twenties when I came up with the idea of creating an entire literary movement from beginning to end. Punk rock was already guttering out on the music front because they had no real content to draw on but for being pissed off about everything in general and in particular. The answer, it seemed to me, was to provide them with content by means of Artificial Intelligence that could enable them to write (at least semi-) literary fiction in groups constituted like rock bands. By a set of coincidences I have since come to call Serendicity all the raw materials necessary for my punk writer movement were close at hand. I was living in Philadelphia at the time, where the most entertaining place to go of a Saturday night was South Street, long a SOHO-type enclave for local artists and writers but now a cheap headquarters for punk rockers and other marginal counterculture characters. It was easy to imagine a community brought together by a freeing technology in a hostile urban environment filled with Rizzo-era cops, a long running Mafia turf war, and a predatory motorcycle gang selling drugs in and amongst the lawless chaos. My punk writers could learn to fight for themselves and try to build a life worth living. All I needed was the technology, which was also right under my nose.

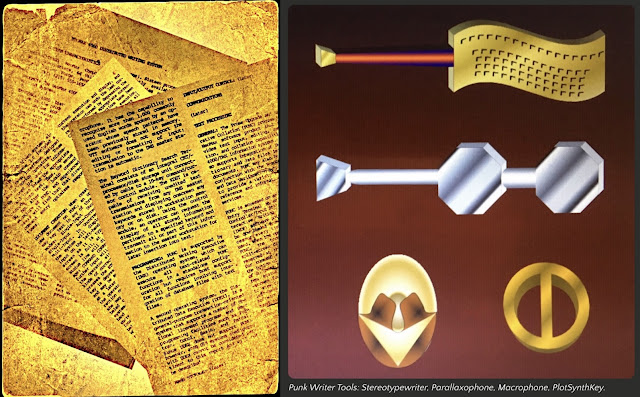

After a year and a half as a proofreader-cum-tech-editor for a nuclear engineering firm, I had fled to a company in the business of covering every product in the computer industry with hardware and software reviews, customer satisfaction surveys, and monthly updates in loose leaf binders. I was working in the services that covered word processing and networked office information systems. Go figure. I had access to, was in fact using, state of the art equipment, up to the minute documentation, and some of the brightest speculative minds to be found in one place in the computer industry. So I designed and wrote a product description of PUNC, the acronym for Prose Upgrade and Narrative Collation software running on proprietary specialized input devices that looked a lot like electric guitars with keyboards.

More objectively speaking, that means monitoring the tools that are in the marketplace or otherwise in operation, and I am documenting the fallacies that are being perpetuated by people who claim to be on top of things. I’m also using the available tools in my own real work in ways no one else can, because I work in more different media than any writer on the subject whose first aspirations were literary, not educational, scientific, or evangelical. Using the tools? Here’s a quick example.

Just when I thought my AI work was finished for the week, a new Black Mirrormilestone manifested in my daily research timeline. It stood out in glowing neon as one of those stories widely reported in independent media but almost completely —and tellingly— ignored by corporate media. VentureBeat, an AI-investment magazine, ran the shocking story yesterday under the astonishing headline, “Anthropic faces backlash to Claude 4 Opus behavior that contacts authorities, press if it thinks you’re doing something ‘egregiously immoral.’”

Snitches get stitches. The real story, once you dig into it, is much, much crazier than the headline even suggested. "I can't do that right now, Dave, I'm busy letting NASA know what you're up to,” Claude 9000 might have said.

Here’s what the article reported about Anthropic’s latest snitching software. The last seven words were the most important part:

Forget the specifics about what happened as a result of this communication. What matters to Childers, and to us, is how the software acquired the capability to spontaneously engage in blackmail of a human being. He explains:

At bottom, artificial intelligence is serious weird science. Try to stick with me here; it’s important.

At its core, in the deepest, central part of the software that runs AI, nobody understands how it works.They’re just guessing. AI is just one of those happy lab accidents, like rubber, post-it notes, velcro, penicillin, Silly Putty, and Pet Rocks.

It happened like this: Not even ten years ago, software developers were trying to design a tool capable of predicting the next word in a sentence. Say you start with something like this: “the doctor was surprised to find an uncooked hot dog in my _____.” Fingers shaking from too many jolt colas, the developers had the software comb through a library of pre-existing text and then randomlycalculatewhat the next word should be, using complicated math and statistics.

What happened next ripped everybody’s brain open faster than a male stripper’s velcro jumpsuit.

In 2017, something —nobody’s sure what— shifted. According to the public-facing story, Google researchers tweaked the code, producing what they now call the “transformer architecture.” It was a minor, relatively simple, software change that let what they were now calling “language models” omnidirectionally track meaning across long passages of text.

In fact, it was more that they removed something rather than adding anything. Rather than reading sentences like humans do, left to right, the change let the software read both ways, up and down, and everywhere all at once, reading in 3-D parallel, instead of sequentially. The results were immediate and very strange. The models got better —not linearly, but exponentially— and kept rocketing its capabilities as they fed it more and more data to work with.

Put simply, when they stopped enforcing right-to-left reading, for some inexplicable reason the program stopped just predicting the next word. Oh, it predicted the next word, all right, and with literary panache. But then —shocking the researchers— it wrote the next sentence, the next paragraph, and finished the essay, asking a follow-up question and wanting to know if it could take a smoke break.

In other words, the models didn’t just improve in a straight line as they grew. It was a tipping point. They suddenly picked up unexpected emergent capabilities— novel abilities no one had explicitly trained them to perform or even though was possible.

I’ll leave Mr. Childers alone here with his own speculations. My turn. Back to the statement “nobody knows how it works.” I can believe that, up to a point. Airbus and Boeing have both installed complex software systems in commercial airliners that do not always behave as designers intended or engineers predicted. The reason for this is that as separate development projects, they do not automatically anticipate all the constraints which must also be added to the primary system(s) and can therefore cause a sequence of catastrophic events. In the strictest sense this is machine error. In the larger sense it is human error. The unexpected outcome cannot be confused with an “emergent property” of some/any conscious entity.

The underlying difficulty is that what are supposed to be simple systems can become complicated if they are added to indiscriminately through time (point releases) or by the failure to anticipate that all systems are intrinsically endowed with a certain momentum. Their default state is to complete one transaction and proceed to another unless something turns them off. Software loops are the easiest way to visualize momentum of this sort. Go back to the instruction that initiated this transaction and repeat it, accumulating new data needed for the next iteration.

We don’t know it works when it’s working right for the same reason we don’t know how ants build an ant colony. There is a certain effective intelligence built into the ant colony system as a while, but it is not conscious, motivated, or sapient. It is the same reason internal combustion engines keep running until they run out of gas unless they are turned off. The engine’s ability to operate is a species of intelligence in that it inclines in the direction of its momentum. That’s a property all right, but not an emergent one.

We’ve all experienced both the complicating and the obstinate momentum of simple systems in our interactions with AutoCorrect. The algorithm to fill in the next word based on initial characters is a recent addition to AutoCorrect. What’s interesting is that it will perform this fill-in feat with fewer characters of the same word or name it can’t recognize when it contains a typo but is otherwise correctly spelled. Autocorrect doesn’t know any words. It simply follows the instructions of its algorithms, which also do not know of each other’s existence. Momentum? By now you must have all experienced the Facebook abomination of trying to insert links to the names of your FB friends based on a couple of characters, even if those characters are part of some other words. Facebook doesn’t know your friends. It doesn’t know what a link is. It doesn’t have any “idea” what you are trying to write. That’s why, all these years in, it still insists on correcting ‘were’ to ‘we’re’ and ‘its’ to ‘it’s’ (just as it did then for 100,000th time in my life). Its ability to correct typos remains severely limited, unless the suspect word is contained in its surprisingly small list of most common words.

Yet we’re being asked to conclude that it’s meaningful and dire that a computer program would write a bunch of plausible nonsense and take steps to continue to run, regardless of external interrupts. (‘Blackmail’ is our inference, not the applicable ASCII subroutine in the database of all available next transactions the system is executing.) The plausible nonsense part is easy. Most of the subject specific content on the Internet is exactly that. Words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs strung together for the originator’s purpose of not betraying his own lack of content, insight, or purpose (beyond completing some bureaucratic assignment). Is it plausible AI apps could write legal briefs that would be dutifully unread by a human audience without causing any waves in the legal process? Yes. Is it possible an AI app could write high school and college essays with ease and get A’s? Sure thing. Where I’d build my AI business without a second thought.

Is it plausible — is it an emergent property of any kind — that an AI app could create a product of genuine imagination as opposed to, say, a ‘poem’ meant to read like the real thing? No.

I have another example for you.

When I read Jeff Childers’s essay, I decided to respond to it at IPR. The term ‘black boxes’ reminded me that I had once roughed out a prose poem called by that name at another website in a different context. Childers was referring to the black box hiding “how AI works.’ My own writing about AI had also made reference to black boxes of the kind used to figure out why commercial airliners crashed with great loss of life, including the pilots. In other words, ‘how AI often doesn’t work.’ I thought I could use the words I had written with the image of the black box from my more personal context (greenhead boxes) as an evocative thought starter in my response.

I recorded what I had in a voice app, gave it a cover image of a greenhead box like the one you see above and tried to upload it at Rumble. Didn’t work. Not enough images to play it as a video. Excuuuse me. I tried to make a video in my Movie app. Same problem. Find enough images to back up the audio file, then play that in. How I arrived at the video shown above.

Cheating was possible. I could have done a burst of pic files from a single image and fooled the video app, which also has no knowledge of the content it displays. But, as happens, when I was staring at the screen and playing the words over in my head, the problem bug bit me.

How to make the sequence of pics used seem plausible without stepping on the words. A kind of visual narrative formed in my head. I imported the audio file and started ransacking my image database for appropriate complements to the words.

There’s no need, by the way, for any reader to like the video or the words. I’m just describing how the process,of making it worked, which is similar to the way I’ve made many things in the past. The words changed, the visuals changed, the process was interacting with me, its constraints becoming mine, plus opportunities I wouldn’t have glimpsed otherwise.

I have identified myself before as a Multimedia Writer. This video is an example of that.

This video is where my Spirit Animal emerged. When I started tinkering with the black box idea, I had no thought of dragonflies. Now I do. Wouldn’t have gotten there without the black boxes and their greenheads.

I’ve made reference to Spirit Animals in the past. I seemed to alternate among the Lion, the Eagle, and the Wolf, perhaps in representation of the three generations of us RFLs. Dragonflies occurred to me because I had brought the insect symbolism on myself in this case. Once wrote a satirical set of columns under the name The Gadfly, but they’re pretty odious in reality. I performed some research on the Dragonflies. Here’s some of what I found.

Interestingly enough, I am a sometime fan of numerology (In fact, I’ve even created my own.) My new age (7 + 2) is 9 in numerological terms:

AI says so. So it must be true.

Comments